A Glorious Past - Indian Cotton

The looms of India's cotton handloom industry have woven fabric that clothed people all over the world, its history beginning almost five centuries ago. Pieces of cotton thread emerged from excavations of the Harappa Civilization which roughly falls between 5000-3500 BC, indicating that woven cotton has been around for far longer than we can even imagine. The golden age of Indian cotton had a long and illustrious run from then till the nineteenth century.

It is a little known fact that cotton manufacturing may have been the secret behind the fabled wealth of India. During the Roman empire, textiles from India were exchanged for Roman gold. In fact, Pliny, the Roman historian from the first century AD complains that India was robbing Rome of all her gold. According to his calculations, the value of imports from India was about a hundred million sesterces (equal to 15 million Indian rupees at the time). Indian cloth was sought after from China to the Mediterranean region and was paid for in silver and gold. Armenian, Arab and Indian traders carried on the trade of cotton fabrics till the 17th century, when large European trading companies began to dominate the region's textile, spice and slave trade by forcibly annexing the producing regions and subsequently colonizing them.

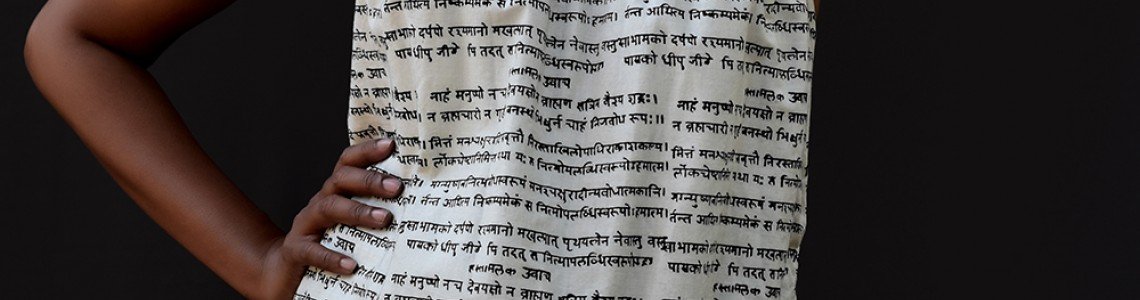

During the time of the golden era of Indian Cotton, cotton was grown, spun and woven all over India. Each region had its own uniqueproduct. Fine textiles werewoven for nobility while ordinary homespun cotton was worn by the common people. A portuguese traveller recounts in 1515 AD that the ships coming from the Gujarat and Coromandel coast carried cloth of thirty different varieties. Ship musters speak of almost 40 different kinds of cotton, with unique names like afta, mulmul, mashru, jamdani, moree, percale, nainsukh, chintz, etc. Muslin or Mulmul was one such fabric that enamoured royalty all over the world. Its soft, sheer texture led Roman emperors to refer to it as "woven wind". In India, mulmul was worn exclusively by Indian royalty. The cotton mulmul produced on Dhaka looms excelled under Mughal patronage. When woven for Viceroys, the muslins were poetically labelled with exotic names like Ab-e-rawan (running water), Shabnam (evening dew) and Sharbati (winelike). The famed muslin was so light and sheer that a common fable recounts Emperor Aurangzeb chiding his daughter Zeb-un-Nisa for appearing in transparent dress in court. She astonished her father by telling him she was in fact wearing seven layers of muslin.

During the time of the golden era of Indian Cotton, cotton was grown, spun and woven all over India. Each region had its own uniqueproduct. Fine textiles werewoven for nobility while ordinary homespun cotton was worn by the common people. A portuguese traveller recounts in 1515 AD that the ships coming from the Gujarat and Coromandel coast carried cloth of thirty different varieties. Ship musters speak of almost 40 different kinds of cotton, with unique names like afta, mulmul, mashru, jamdani, moree, percale, nainsukh, chintz, etc. Muslin or Mulmul was one such fabric that enamoured royalty all over the world. Its soft, sheer texture led Roman emperors to refer to it as "woven wind". In India, mulmul was worn exclusively by Indian royalty. The cotton mulmul produced on Dhaka looms excelled under Mughal patronage. When woven for Viceroys, the muslins were poetically labelled with exotic names like Ab-e-rawan (running water), Shabnam (evening dew) and Sharbati (winelike). The famed muslin was so light and sheer that a common fable recounts Emperor Aurangzeb chiding his daughter Zeb-un-Nisa for appearing in transparent dress in court. She astonished her father by telling him she was in fact wearing seven layers of muslin.

Until colonial times, cotton was handspun at home by rich and poor alike. Millions of women spun cloth at home, the richer ones spun as a hobby while the poorer women spun for a living. But the demise of this flourishing industry was drawing near. In 1600 AD, the East India Company was granted exclusive rights for trade between India and Britain. Textiles made up the bulk of this trade, all paid for in bullion: in four years alone between 1681 and 1685 the East India Company imported 240 tonnes of silver and 7 tonnes of gold into India. The demand for the superior cloth from India grew so large that it began to affect British weavers negatively. Finally in response to the protesting weavers, a duty of 75 % was levied on Indian imports. This was the beginning of the end. Systematically over a period of a mere 100 years, India was reduced to exporting its superior cotton and importing machine woven cloth.

"The story of cotton in India is not half told," writes Francis Carnac Brown, a British cotton planter in the Malabar region of India, "how it was systematically depressed from the earliest date that American cotton came into competition with it about the year 1786, how for 40 or 50 years after, one half of the crop was taken in kind as revenue, the other half by the sovereign merchant at a price much below the market price of the day which was habitually kept down for the purpose, how the cotton farmer's plough and bullocks were taxed, the Churkha taxed, the bow taxed and the loom taxed; how inland custom houses were posted in and around every village on passing which cotton on its way to the Coast was stopped and like every other produce taxed afresh; how it paid export duty both in a raw state and in every shape of yarn, of thread, cloth or handkerchief, in which it was possible to manufacture it; how the dyer was taxed and the dyed cloth taxed, plain in the loom, taxed a second time in the dye vats, how Indian piece goods were loaded in England with a prohibitory duty and English piece goods were imported into India at an ad valorem duty of 2 ½ per cent. It is my firm conviction that the same treatment would long since have converted any of the finest countries in Europe into wilderness. But the Sun has continued to give forth to India its vast vivifying rays, the Heavens to pour down upon the vast surface its tropical rains. These perennial gifts of the Universal Father it has not been possible to tax."

As history teaches us, it was Mahatma Gandhi who was able to see the role that handspun fabric had played in the past and revived the craft as a symbol of independence, thus giving birth to the Cotton movement.

Today, the story of colonization is far behind us and the world has become a global village with each of us bearing a common load of problems of deforestation and pollution and the like. With industrialization came the need for faster growth with little thought given to the social and ecological cost it would come at. Today, the world looks for renewable energy and search is on for sustainable methods of manufacturing. It might yet be that handspun, handwoven fabrics come back to the forefront of the textile industry leaving behind the machine made, one-size-fits-all mass manufactured cloth.

Natsy by Design invites you to partake in history and revel in the wonders of the Indian handloom industry. Hand-woven sarees, dupattas and stoles, well-cut and tailored dresses and tunics in airy fabrics such as mulmul, chanderi and cotton and a selection of revival weaves that are reminiscent of the golden era of Indian fabric. Available at www.natsybydesign.com/apparel

(photo: courtesy SHAHIDUL ALAM / DRIK - Woven of nearly transparent Bengal muslin, this angarkha, or long, open-fronted men's tunic, belongs to the Weavers Studio Resource Centre in Kolkata, India - http://www.aramcoworld.com/)

Leave a Comment