The Art of Shibori Tie and Dye

In Japan, the earliest known example of cloth dyed with a shibori technique dates from the 8th century. It is among the goods donated by the Emperor Shōmu to the Tōdai-ji in Nara. Until the 20th century, not many fabrics and dyes were in widespread use in Japan. The main fabrics were silk and hemp, and later cotton. The main dye was indigo and, to a lesser extent, madder and purple root. Shibori and other textile arts, such as Tsutsugaki, were applied to all of these fabrics and dyes. In an attempt to enhance the traditional tie and dye skills of our artisans, new tie and dye methods from Japan and Indonesia were introduced, resulting in stunning hand-crafted textiles.

In traditional Shibori crafts, artisans have long been known to devise ways in which the handwork finds the most efficient route to achieve its production goal. They attend to the smallest detail, such as the choice of a tying thread. For Miura-Shibori they use a loosely twisted medium-fine cotton thread wound on its own ball; for Boshi-Shibori they use a tightly twisted medium cotton thread wound on a wooden dowel; and for Kumo-Shibori a medium-heavy linen thread wound on a wooden dowel and soaked in water (see details below). Sometimes, the thread is deliberately changed to a different size in order to create a specific design effect.

In traditional Arashi-Shibori, a slightly tapered, 12-ft long, polished wooden pole is used to wind a narrow, long kimono cloth (14 inches by 12 yards) diagonally upon itself. The cloth on the pole is then wound with a tying thread that contributes to making small, puckered creases where the cloth is pushed and scrunched on the pole.

Dyeing of these bolts of shaped cloth on the long heavy pole takes two strong men and a large trough-like vat. This esoteric process has been modified to suit the lifestyle of artists in both Japan and the U.S.A. In Shibori there is a “right way” to do things, but, at the same time, there hardly exists a wrong way. The traditional way gives contemporary artists a framework not only to explore shaping methods but also to modify the materials and tools.

The unique effects possible with Nui-Shibori are determined by the type of stitch, whether or not the cloth is folded, and the arrangement of the stitches-straight, curved, parallel, or area enclosing. After the stitching of a piece is completed, the cloth is drawn into tight gathers, along the stitched thread(s), and secured by knotting. It is then dyed. The cloth within the gathers is largely protected from the dye. The simple running stitch is commonly used and sewn evenly in a constant forward movement. The only other type of stitch used in Japanese Shibori is an overcast stitch called Makinui. This stitch is made over the edge of a fold of cloth, and stitching proceeds from right to left with a circular motion of the needle. The thread is not drawn up with each stitch, but the cloth is gathered on the needle. As the stitching continues, the gathered cloth is pushed back over the eye of the needle onto the thread.

Stitching affords flexibility and control to create designs of great variety-delicate or bold, simple or complex, pictorial or abstract. In fourteenth-century Japan, stitching was explored in combination with brush painting and gold leaf stenciling, as well as delicate embroidery, to reproduce stylized motifs from nature, creating an exciting fashion for noble ladies and warriors. During the past few decades, artisans and designers – not just in Japan but also beyond – have been reinterpreting these traditional processes and patterns into modern fashion idioms, expanding the choice of materials, the size of design elements, and the finishing process from traditional dyeing into modern chemical treatments.

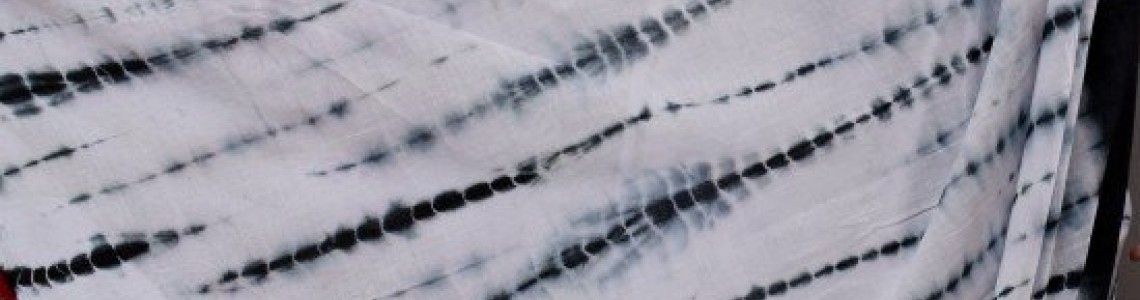

Natsy By Dseign brings you a selection of Shibori apparel range called Jaldhara, intricate resist dyeing silhouettes fashioned after the River of Life. The wave like lines of the dye is reflective the ebb and flow of the river.

Leave a Comment