Roadmap to Enlightenment

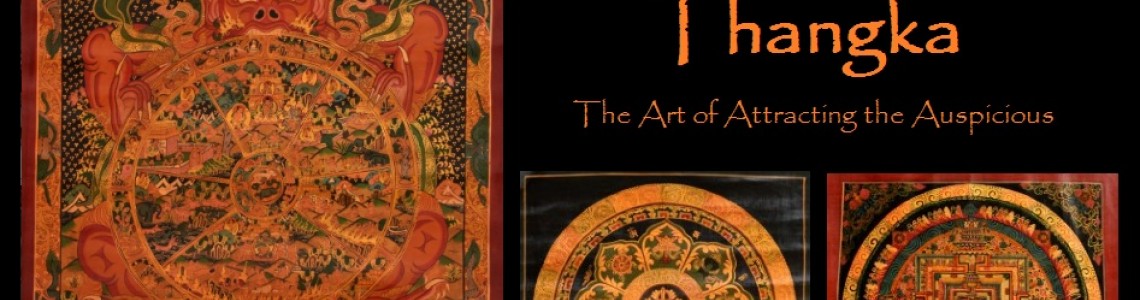

A thangka is a Tibetan Buddhist scroll painting on cotton or silk appliques. The paintings usually depict Buddhist deities or mandalas (a circular figure representing the universe in Hindu or Buddhist symbolism). The Tibetan word “thangka” comes from a combination of two words - “than” meaning flat and “ka” meaning painting. Some scholars suggest ‘thangka’ in ancient Tibetan meant “thing that one unrolls”. The painting is done on a flat surface and can rolled up when not being displayed. Thangka paintings are messages meant to communicate Buddhist philosophy and were used for instruction or for personal meditation. Each detail in the painting has deep meaning and points to various aspects of Buddhist philosophy. Traditionally the paintings are kept rolled up, but during festivals such as Losar and Tibetan New Year, monasteries unroll the scrolls they own - usually applique thangkas for public viewing and ceremony.

The sacred art of thangka painting dates back to the 7th century. Originating in Nepal, the art form evolved into several schools of painting. Centuries ago, these thangka scrolls served as the medium through which monks taught the Buddhist tradition to villagers. The paintings could be easily transported and unrolled in villages far from the monastery. Villagers would gather in the main square around the lama (or teacher). He would then proceed to teach them about the life and teachings of Buddha, pointing with a stick at the different parts of the thangka to illustrate his stories.

The thangka art form developed alongside the Buddhist wall paintings as seen in the Ajanta Caves in India and the Magao Caves on the Silk Road. Thangkas were usually commissioned by individuals who would either retain the painting for themselves or donate it to a monastery. Commissioning a thangka is considered a means of generating spiritual merit, and many times, if an individual is facing some kind of hardship, a lama is consulted and he recommends the creation of a thangka of a specific deity as a remedy. The artist then designs a thangka by referring to the measurements of deities detailed in the scriptures, following the prescription of the lama.

Thangkas usually have detailed compositions and include many tiny and intricate figures. A central deity is often surrounded by other identified figures in a highly symmetrical composition. Symmetry is a very important feature of thangka paintings. Proportions and measurements of each deity have been established by artistic practice and Buddhist iconography and a thangka artist must work from this exact knowledge. A grid representing these proportions has established correct transmission and continuity of the figures. Deities shown in thangka paintings usually depict visions that Buddhist spiritual masters saw during their meditations. These visions were then recorded and incorporated into the scriptures. Hence the proportions are considered sacred since they are the visual expression of spiritual realities.

The beautiful art form of thangka paintings is preserved and passed on through the lineage of thangka masters and their students, who after years of training become masters themselves, thereafter passing on the legacy to others. Often the lineage remained in families, being passed on from father to son. Thargey-la, a master painter pictured here comes from a thangka lineage that goes back to eight generations of painters. Aspiring thangka artists must spend years studying the zations that occurred at the time of a vision. The paintings are thus a two-dimensional medium illustrating a multi-dimensional spiritual reality. Practitioners use thangkas as a sort of road map to guide them to the original insight of the master. This map must be accurate and it is the responsibility of the artist to make sure it is so in order for a thangka to be considered genuine, or to be useful as a support for Buddhist practice, guiding one to the proper place.

The first step of making a thangka is stitching a piece of canvas onto a wooden frame. It is prepared with a mixture of chalk, gesso, and base pigment, and rubbed smooth with a glass until the texture of the cloth is no longer apparent. The outline of the deity is sketched in pencil onto the canvas using iconographic grids, and then outlined in black ink. Powders composed of crushed mineral and vegetable pigments are mixed with water and adhesive to create paint. Some of the elements used are quite precious, such as lapis lazuli for dark blue. Landscape elements are blocked in and shading is applied using both wet and dry brush techniques. Finally, a pure gold paint is added, and the thangka is framed in a precious brocade border. A standard thangka takes an artist about six weeks to complete.

Though thangka paintings served various functions during public worship, teaching and ceremony, most importantly they are a tool for meditation to help bring a person further down the path of enlightenment. The buddhist practitioner uses the painting to imagine themselves as a particular deity thereby “internalizing the Buddha qualities.” Thangka paintings are thus a visual expression of the highest state of consciousness, which is the ultimate goal of the Buddhist spiritual path. Hence thangkas have earned themselves the title “roadmap to enlightenment” as they show you the way to this fully awakened state of enlightenment. Thangkas hang on or beside altars, and may be hung in the bedrooms or offices of monks and other devotees.

(Images and references courtesy http://www.tibetan-buddhist-art.com/, http://www.norbulingka.org/)

Leave a Comment