Articulating Cultural Identity

Support a heritage that is being kept alive by artisans under adverse circumstances

-2200x920.jpg)

Artisan Collective

We are committed to ensuring that the artisans who make the product are paid a fair price

-2200x920.jpg)

India Abundant

Over 1000 mindfully curated or co-created hand-crafted treasures made in India

Curated Craft Trails

Collaborating with over 100 Master Craftsmen and Women and as many craft traditions

Top Categories

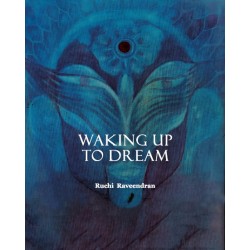

Waking up to Dream by Ruchi RaveendranFiction | Short Stories | Art Hardcover - 8X10 inchesISBN - 9781492032649Published by Of Indian Origin Waki..

₹ 999.00

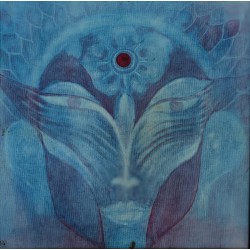

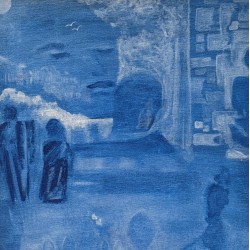

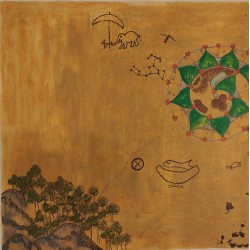

Ex Tax:₹ 999.00VishnuAcrylic on Canvas - Painting by Ruchi RaveendranOriginal Size: 16x16 inchesPrint Size: : 15x15 inches..

₹ 22,000.00

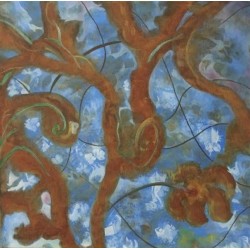

Ex Tax:₹ 22,000.00Memories of the BanyanAcrylic on Canvas - Painting by Ruchi RaveendranOriginal Size: 20x20 inchesPrint Size: : 15x15 inches..

₹ 45,000.00

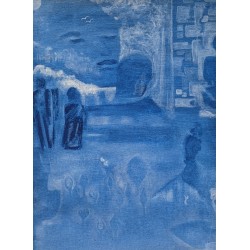

Ex Tax:₹ 45,000.00KailasaAcrylic on Canvas - Painting by Ruchi RaveendranOriginal Size: 12x16 inchesPrint Size: : 10x15 inches..

₹ 25,000.00

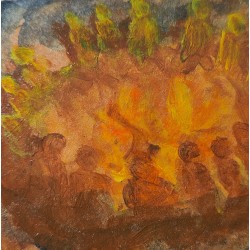

Ex Tax:₹ 25,000.00The RitualAcrylic on MDF - Painting by Ruchi RaveendranPrint Size: : 10x15 inchhes..

₹ 1,500.00

Ex Tax:₹ 1,500.00KumbhamAcrylic on MDF - Painting by Ruchi RaveendranPrint Size: : 10x15 inches..

₹ 1,500.00

Ex Tax:₹ 1,500.00Waking up to Dream by Ruchi RaveendranFiction | Short Stories | Art Hardcover - 8X10 inchesISBN - 9781492032649Published by Of Indian Origin Waki..

₹ 999.00

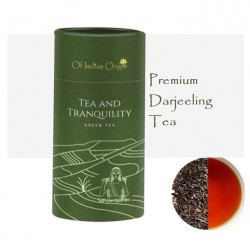

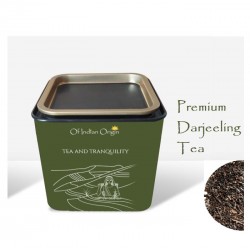

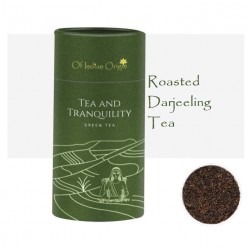

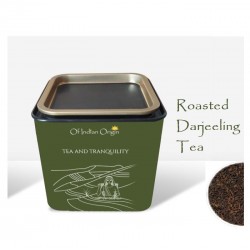

Ex Tax:₹ 999.00Darjeeling Tea is considered to be one of the most prized teas in the world and the region yields several seasonal flushes through the year. Each Flus..

₹ 341.25

Ex Tax:₹ 325.00Darjeeling Tea is considered to be one of the most prized teas in the world and the region yields several seasonal flushes through the year. Each Flus..

₹ 294.00

Ex Tax:₹ 280.00

Brand: Aroma World

Orange Essential OilVolume - 30 mlCare Instructions: Please do not use undiluted. Always use with a carrier oil. Please consult with an aroma th..

₹ 100.00

Ex Tax:₹ 100.00

Brand: Aroma World

Pine Essential OilVolume - 10 mlCare Instructions: Please do not use undiluted. Always use with a carrier oil. Please consult with an aroma ther..

₹ 100.00

Ex Tax:₹ 100.00

Brand: Aroma World

Basil Essential OilVolume - 10 mlCare Instructions: Please do not use undiluted. Always use with a carrier oil. Please consult with an aroma..

₹ 100.00

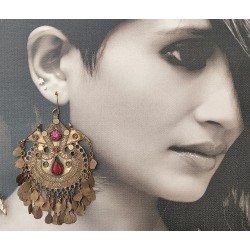

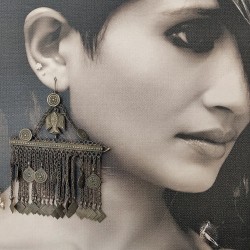

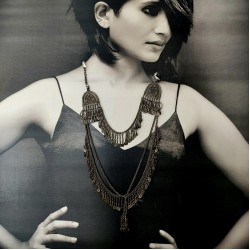

Ex Tax:₹ 100.00Antique Brass Kajaldani NeckpieceMaterial: BrassCare: Avoid exposure to moisture. Wipe with a soft cotton cloth after use.Note: Items bought..

₹ 3,090.00 ₹ 4,120.00

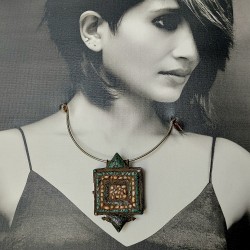

Ex Tax:₹ 3,000.00Antique Ghau Prayerbox PendantA Ghau is a Tibetan Buddhist amulet container or prayer box, usually made of metal. When worn as jewellery its also..

₹ 4,120.00 ₹ 6,180.00

Ex Tax:₹ 4,000.00Antique Ghau Prayerbox Pendant

A Ghau is a Tibetan Buddhist amulet container or prayer box, usually made of metal. When worn as jewellery its al..

₹ 5,150.00 ₹ 9,270.00

Ex Tax:₹ 5,000.00Antique Tribal Brass Anklet Refashioned into a PendantMaterial: BrassCare instructions: Avoid exposure to moisture. Wipe with a soft cotton cloth..

₹ 3,090.00 ₹ 4,120.00

Ex Tax:₹ 3,000.00Antique Tribal Brass Anklet Refashioned into a PendantMaterial: BrassCare instructions: Avoid exposure to moisture. Wipe with a soft cotton cloth..

₹ 3,090.00 ₹ 4,120.00

Ex Tax:₹ 3,000.00Antique Tribal Brass Anklet Refashioned into a PendantMaterial: BrassCare instructions: Avoid exposure to moisture. Wipe with a soft cotton cloth..

₹ 5,150.00 ₹ 7,725.00

Ex Tax:₹ 5,000.00Inspiration

#SupportArtisans

We are committed to paying the artisans a fair price and ensure that upto 70% of what we earn goes back to the artisans. We work with several organisations who engage people with disabilities, or work with underprivileged women, or tribal communities to produce craft that secures a source of livelihood for them. We believe in promoting organic, eco-friendly products, and encourage sustainable fashion.

What our patrons are saying

What really fuels our passion for bringing you the best of hand-crafted products is the testimonials from our patrons. A simple line of encouragement goes a long way in wanting to do better with every step forward.

What can I say... Emptied my wallet and will be back for more! Absolutely fabulous stuff.

- Aarti Rao Shetty - Singer, Music Curator, Restaurateur

A walk through the studio is like a lesson in Indian History. Each piece has a story. I am in awe.

- Shilpi Chowdhury - Celebrity Haute Couture Designer and History Professor

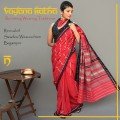

The saree is more beautiful than I thought. U have a great collection. Keep it up.

- Shilpa Jaiswal

I loved the sarees - they are simply wonderful. And the silver earrings are the best - what workmanship and so beautifully crafted.

- Mahua Chinappa - PR Professional, Blogger, Influencer

I received the goodies. They are exquisite and so beautiful.

- Damyanti Ghosh - Crime Novelist, Social activist

Liked Natasha who is so passionate about her products. Loved the hand-picked items from artisans across India - apparel, collectables, jewellery, and more!

- Uma Money - Networking Professional

My first purchase from natsy and it was perfect. The product quality was good and delivery was on time.

- Sarbani Bhattacharya - Artist, Dancer, Social Worker

The packing is really nice and the products are awesome. I like the dupattas and the kurti is correctly fitted. The saree is excellent.

- Mala Sanyal

OMG OMG!! This site is just fantastic!! I am going crazy looking at the stuff- the bags, the sarees, the paintings...yummm!!

- Ruchi Gopalakrishnan - IT professional

My purchases are all the more special since I know Natasha actually meets with the artisans and picks every piece herself.

- Deepa Subbaraman Sriram - Saree aficionado, Social influencer

What an amazing collection of Indian artifacts. Its difficult to resist buying far more than I take away today...

- Kamalinee Natesan - Author, French Teacher

Well sourced style at good prices. Spent hours exploring all the Indian crafts and arts

- Mary Coates - Indophile, Curio shop Owner from UK

The products are sourced from around the country, having intriguing back-stories. Natasha is familiar with each individual piece, and these are offered for sale only when they meet her exacting standards.

- Sonali Bhatia

Everything is so pretty. I can't get enough of it. Lovely jewelry.

- Kim Samuel

I love your collection of antique jewellery and vintage collectables. Just my kind of stuff.

- Inderpreet Nagpal - Chef

Absolutely gorgeous stuff. I have bought so many paintings I have run out of walls in my house.

- Madhu Ganguly - Art collector, IT professional

You have so much passion for the art and crafts of India and it shows in your wwork. I am so proud of you. And super happy with my saree.

- Shyamili Satyendran - HR professional

Its become a ritual now that I get all my festival sarees from you. And as usual my friends in the Indian community here are always wowed.

- Sumona - Teacher, US

The gypsy in me revels at the collection here. There is just so much energy and spirit in the products that you curate, gives me so much pleasure.

- Elizabeth Nunes - Author, Dancer, Healer - Portugal

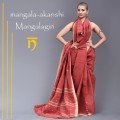

Aspiration

#lookbook

We constantly strive to bring you products that are unique and bring out the best of the craft and the craftsmen and women. Every product is mindfully curated or co-created hoping to find a place in your home and take its story forward.

From the Blog

ofindianorigin

47

14549

STEP 1UNDERSTANDING

PUBLISHING Editing the bookCost 10,000 – 30,000 depending on

the length of the book as well as no. of edits / revisions. This will include

back cover blurb, verso page, contents pa..

admin

230

22461

Barnalee Sarkar has been practicing and studying Indian classical dances for over 30 years. Formerly a student of Nrityagram founded by the late Pratima Gauri, who has been an enduring influence in he..

admin

18

21628

Startup India

is a flagship initiative of the Government of India, intended to build a strong

ecosystem that is conducive for the growth of startup businesses, to drive

sustainable economic growth and..

NatashaAcharya

23

29188

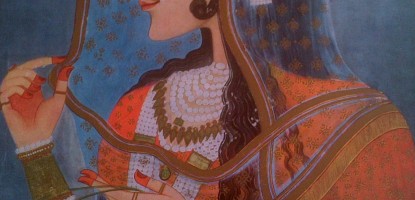

In the 18th century the art of miniature painting had become quite popular in the Rajput states. Ateliers were maintained not only at the courts of the Rajput rulers, but artists were also in the empl..

admin

286

26057

The festive season is here and with it many occasions to dress up and celebrate with friends and family. Find inspiration for your look this season in the enthralling world of art. Here are 10 looks ..